The following is the first part of a lengthy consideration of the idea of the Hashtag Revolution as a model for a social/political movement. This section considers mainly the Occupy movement, and the next section considers the relevance of the concept of the hashtag revolution to the presidential elections.

The following is the first part of a lengthy consideration of the idea of the Hashtag Revolution as a model for a social/political movement. This section considers mainly the Occupy movement, and the next section considers the relevance of the concept of the hashtag revolution to the presidential elections.

The hashtag revolution or hashtag revolt is a phrase coined by Jeff Jarvis to capture the idea of a movement organized around a hashtag, given that “a hashtag has no owner, no hierarchy, no canon or credo. It is a blank slate onto which anyone may impose his or her frustrations, complaints, demands, wishes, or principles.”

The Occupy movements both in NYC and around the world, as well as many of the Arab Spring movements, are mobilized by Twitter, publicized on Twitter, and reported live on the ground via participants with mobile phones. But I would agree with those who deny that the movement is some kind of spontaneous result of Twitter. There is an air of techological determinism, and technological fetishism about this claim that could use some thoughtful de-bunking. It seems that the importance of Twitter to the Occupy movement is not that it created or allowed for these movements, but that the structure and the practices of use Twitter encourages complement the structures and practices of a new culture of civic and political engagement.

The structure of the hashtag: parallels with the structure of the Occupy movement

The hashtag is a means of meta-labeling of a message in order to help organize a conversation and make it accessible to others.

In the context of the free-for-all of Twitter messages, the hashtag is one of the primary ways of organizing Tweets and making them accessible to anyone who wishes to “track” a single topic or conversation. This is essentially a means of artificially inserting a searchable keyword into a message without needing to use it within the actual message of the Tweet. These keywords are used to create a sort of topically organized forum of discussion without any kind of “group” or pre-organized forum of individuals- thus making the conversation open and accessible to anyone on Twitter who knows or thinks to search that key-phrase.

These labels are often either developed and adopted naturally by the general need for a common hashtag, or special events or groups may take the initiative to develop or promote a new hashtag. Interestingly, these tags are often surprisingly insular and non-intuitive; even if you are able to find out about them from the outside, it is not always clear what any given hashtag actually stands for. Some examples of this include #socent, for social enterprise, or the practice of labeling the Arab Spring movements for specific days of action (even long after the day has happened), such as #Jan25 or #J25 for the first day of protests in Tahrir Square. The name of this Occupy movement was generated as a hashtag in the first place, by the anticonsumerism magazine Adbusters. This helps to suggest something about the nature of this movement as based on a highly organized and strategic utilization of social media, intentionally meant to make the movement widely accessible. I will return to a consideration of the importance of the strategic use of new media to the Occupy movement later.

The hashtag is the encapsulation of an entire public and widely distributed conversation in a single word or phrase.

The Occupy movement, similarly, can be seen as the ultimate distillation of a conversation which has been running strong since Marx, and been reframed and brought back into consideration since the “Great Recession” starting in 2008.

The concept of the 99% versus the 1% is a powerful one, and incorporates a wide range of experiences. The famous tumblr blog, “We are the 99%” features the stories and images of regular civilians who identify with the hardship and struggles of the lower and middle classes. If anything, the main message of the Occupy movement is precisely the development of awareness and recognition about these stories and individuals, and mobilization around this fluid yet common experience. This message is easy to sympathize with, even if it is not quite clear why it demands the occupation of public space. I would even argue that in some ways we can see the influence of this awareness and dialogue strongly in the 2012 elections, with the “middle class” being the buzzword of the debates and campaign pitches. (I will return to draw out the differences between these discourses of the political institutions and the Occupy movement later).

Yet the hashtag of the #99percent and #occupy are not quite synonymous. The former one actually contains a centralized message of some kind- whereas the hashtag #occupy is more like a self-referential, contentless label. I want to argue that the actual Occupation movement is anchored by a divorce from any concrete, singular message or demands.

A hashtag is subject to derailments, to disorganization and trolling by virtue of the very accessibility of this hashtag. Even if the hashtag is generated and promoted by a group with a unified message, anyone may use the hashtag and be visible within the stream of conversation, even if they want to promote an opposing or destabilizing message.

One of the earliest truly public discussions of the Occupy movement, occurring on the Adbuster’s website in July 2011, involved the call for an occupation of 20,000 bodies, and a movement styled upon that of Tahrir Square- ie, a populist movement with a single demand or ultimatum. The article asks the question (featured on the poster above), “What is our one demand?”

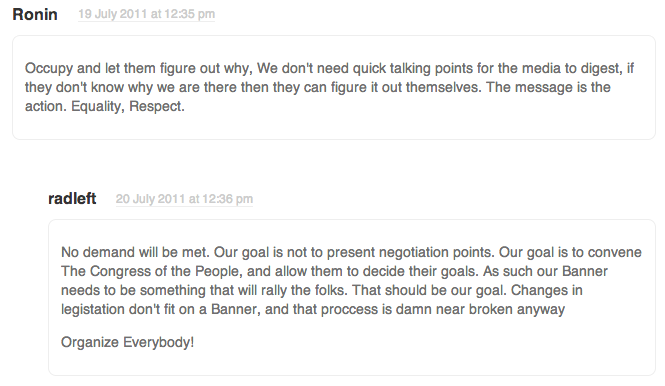

The writers of the article propose their own demand: that Barack Obama ordain a Presidential Commission tasked with ending the influence money has over our representatives in Washington. It’s time for DEMOCRACY NOT CORPORATOCRACY.” Yet they also end the article asking for comments suggesting what this one demand should be. The outpouring of discussion that happens in the hundreds of comments on this article perfectly represent the nature of the #occupy discourse: a fine blend of tactical planning, directing occupiers to Facebook pages and Reddit to continue the discussion and planning for the days of occupation, people showing support for the spirit of the occupation, and of course hundreds of suggestions for different possible demands of the occupiers, ranging from #endlesswar to feminist advocacy to ending corporate personhood….to a consideration of whether demands are counterproductive to the entire occupation:

Comments like these abound on this early posting, and were developed and propagated as an a theoretical underpinning of the occupation by Occupiers, as well as the likes of activist-academics such as David Graeber and Judith Butler.

The ultimate irony of Occupy as a hashtag revolution, highly organized and accessible though it is as a symbol, is at its very roots a movement confused about it’s essential message- or whether there ought to be an essential message at all.

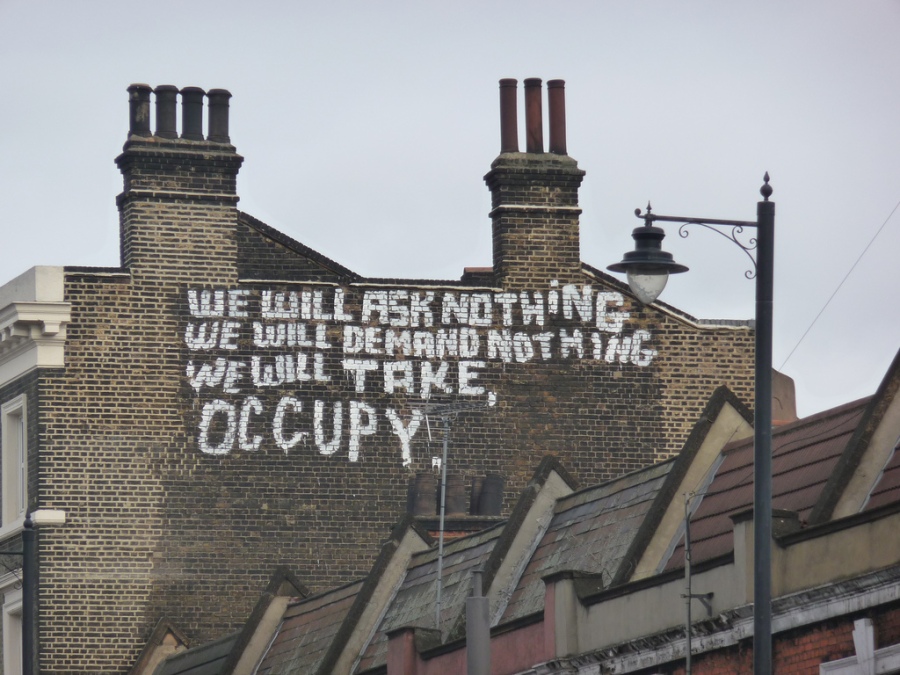

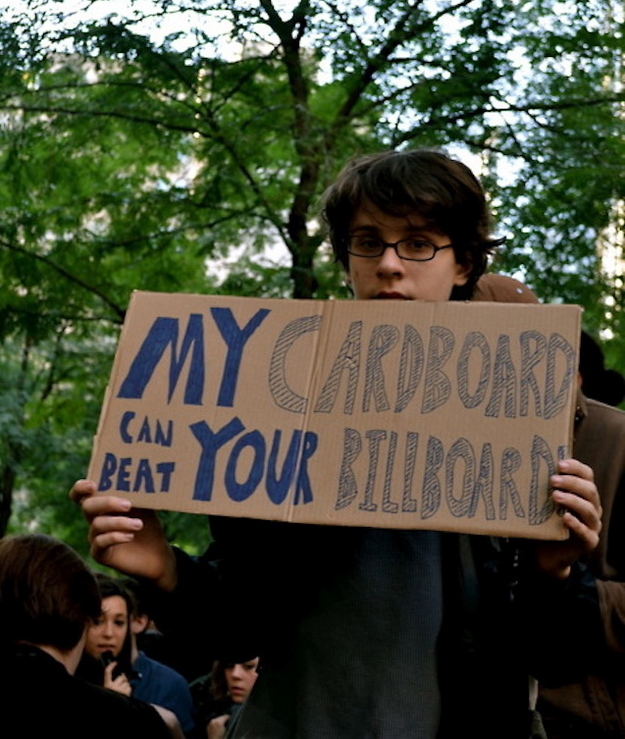

Like the Iamthe99percent tumblr, another highly visible symbol of the Occupy movement was its plethora of signs. These signs, like the stories told by the individuals on tumblr, like those tweeting under the sign of the occupy hashtag, are individually made, yet publicly broadcast messages of protest and solidarity.

Structurally similar to a hashtagged tweet in their brevity and personal-broadcast nature, these messages are unified and organized not by a textual label, but by the actual act of Occupation. These signs provide an interesting conceptual linkage between the virtual act of support and awareness and the physical act of protest and occupation. It is important to understand this linkage, because I think it is fundamental to the nature of this social movement.

As an open-ended protest, constituted by individual messages, even those dedicated individuals who are physically occupying the space do not really have any more authority over the movement than any other individual, present or not. This means that the physical occupation becomes an extension of the boundless dialogue happening online.

I believe it is this structure- this unique linkage of the online and offline occupation- that makes this movement so powerful and so significant. In my terms, a theory of occupation involves the creation of individual interactions unmediated by “corporate media”, of shared spaces of dialogue, and public visibility. It is true that the movement would not be the same without a physical occupation- but it is equally true that it would not be the same without the media- and social media coverage of the physical occupation. The hashtagged messages and the cardboard signs of the Occupiers are in a sort of feedback loop of awareness and public dialogue- a loop further extended and made more accessible by its mystery, the lack of the centralized message forcing both Occupiers and its general media-audience to ask itself: What is wrong here?, and, What can be done to fix it?

It is not actually any particular philosophy or political standpoint that dominates this conversation, but rather the discussion and exploration of the possibility of true global “revolution”, of citizens coming together independently of existing institutions of society and government to create a better world. The open ended question of “What is there demands?” becomes a question of, “What are our demands?” This is the beauty of the hashtag revolt.

It’s difficult to find knowledgeable people on this topic, but you seem like you know what you’re talking about!

Thanks